Shigella are bacteria that can infect the digestive tract and cause a wide range of symptoms, from diarrhea, cramping, vomiting, and nausea, to more serious complications and illnesses. Infections, called shigellosis, sometimes go away on their own; in others, antibiotics can shorten the course of the illness.

Shigella are bacteria that can infect the digestive tract and cause a wide range of symptoms, from diarrhea, cramping, vomiting, and nausea, to more serious complications and illnesses. Infections, called shigellosis, sometimes go away on their own; in others, antibiotics can shorten the course of the illness. Shigellosis, which is most common during the summer months, typically affects kids 2 to 4 years old, and rarely infects infants younger than 6 months old.

These infections are very contagious and can be prevented with good hand washing practices.

Signs and Symptoms

Shigella bacteria produce toxins that can attack the lining of the large intestine, causing swelling, ulcers on the intestinal wall, and bloody diarrhea.

The severity of the diarrhea sets shigellosis apart from regular diarrhea. In kids with shigellosis, the first bowel movement is often large and watery. Later bowel movements may be smaller, but the diarrhea may have blood and mucus in it.

Other symptoms of shigellosis include:

- abdominal cramps

- high fever

- loss of appetite

- nausea and vomiting

- painful bowel movements

In very severe cases of shigellosis, a person may have convulsions (seizures), a stiff neck, a headache, extreme tiredness, and confusion. Shigellosis can also lead to dehydration and in rare cases, other complications, like arthritis, skin rashes, and kidney failure.

Some children with severe cases of shigellosis may need to be hospitalized.

Contagiousness

Shigellosis is very contagious. Someone may become infected by coming into in contact with something contaminated by stool from an infected person. This includes toys, surfaces in restrooms, and even food prepared by someone who is infected. For instance, kids who touch a contaminated surface such as a toilet or toy and then put their fingers in their mouths can become infected. Shigella can even be carried and spread by flies that have touched contaminated stool.

Because it doesn't take many Shigella bacteria to cause an infection, the illness spreads easily in families and child-care centers. The bacteria may also spread in water supplies in areas where there is poor sanitation. Shigella can be passed in the person's stool for about 4 weeks even after the obvious symptoms of illness have resolved (although antibiotic treatment can reduce the excretion of Shigella bacteria in the stool).

Prevention

The best way to prevent the spread of Shigella is by frequent and careful hand washing with soap, especially after they use the toilet and before they eat. This is especially important in a child-care setting.

If you're caring for a child who has diarrhea, wash your hands before touching other people and before handling food. (Anyone with a diarrhea should not prepare food for others.) Be sure to frequently clean and disinfect any toilet used by someone with shigellosis.

Diapers of a child with shigellosis should be disposed of in a sealed garbage can, and the diaper area should be wiped with disinfectant after use. Young children (especially those still in diapers) with shigellosis or with diarrhea of any cause should be kept away from other kids.

Proper handling, storage, and preparation of food can also help prevent Shigella infections. Cold foods should be kept cold and hot foods should be kept hot to prevent bacterial growth.

Diagnosis and Treatment

To confirm the diagnosis of shigellosis, your doctor may take a stool sample from your child to be tested for Shigella bacteria. Blood tests and other tests can also rule out other possible causes of the symptoms, especially if your child has a large amount of blood in the stool.

Some cases of shigellosis require no treatment, but antibiotics often will be given to shorten the illness and to prevent the spread of bacteria to others.

If the doctor prescribes antibiotics, give them as prescribed. Avoid giving your child nonprescription medicines for vomiting or diarrhea unless the doctor recommends them, as they can prolong the illness. Acetaminophen (such as Tylenol) can be given to reduce fever and make your child more comfortable.

To prevent dehydration, follow your doctor's guidance about what your child should eat and drink. Your doctor may recommend a special drink called an oral rehydration solution, or ORS (such as Pedialyte) to replace body fluids quickly, especially if the diarrhea has lasted 2 or 3 days or more.

Children who become moderately or severely dehydrated or those with other more serious illnesses may need to be hospitalized to be monitored and receive treatment such as intravenous (IV) fluid therapy or antibiotics.

When to Call the Doctor

Call the doctor if your child has signs of a Shigella infection, including diarrhea with blood or mucus, accompanied by abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, or high fever.

Children with diarrhea can quickly become dehydrated, which can lead to serious complications. Signs of dehydration include:

- thirst

- irritability

- restlessness

- lethargy

- dry mouth, tongue, and lips

- sunken eyes

- a dry diaper for several hours in infants or fewer trips to the bathroom to urinate in older children

If you see any of these signs, call the doctor right away.

Scarlet fever is caused by an infection with group A streptococcus bacteria. The bacteria make a toxin (poison) that can cause the scarlet-colored rash from which this illness gets its name.

Scarlet fever is caused by an infection with group A streptococcus bacteria. The bacteria make a toxin (poison) that can cause the scarlet-colored rash from which this illness gets its name.  A salmonella infection is a foodborne illness caused by the salmonella bacteria carried by some animals, which can be transmitted from kitchen surfaces and can be in water, soil, animal feces, raw meats, and eggs. Salmonella infections typically affect the intestines, causing vomiting, fever, and other symptoms that usually resolve without medical treatment.

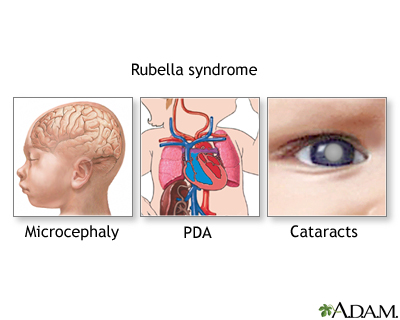

A salmonella infection is a foodborne illness caused by the salmonella bacteria carried by some animals, which can be transmitted from kitchen surfaces and can be in water, soil, animal feces, raw meats, and eggs. Salmonella infections typically affect the intestines, causing vomiting, fever, and other symptoms that usually resolve without medical treatment.  Rubella — commonly known as German measles or 3-day measles — is an infection that primarily affects the skin and lymph nodes. It is caused by the rubella virus (not the same virus that causes measles), which is usually transmitted by droplets from the nose or throat that others breathe in. It can also pass through a pregnant woman's bloodstream to infect her unborn child. As this is a generally mild disease in children, the primary medical danger of rubella is the infection of pregnant women, which may cause congenital rubella syndrome in developing babies.

Rubella — commonly known as German measles or 3-day measles — is an infection that primarily affects the skin and lymph nodes. It is caused by the rubella virus (not the same virus that causes measles), which is usually transmitted by droplets from the nose or throat that others breathe in. It can also pass through a pregnant woman's bloodstream to infect her unborn child. As this is a generally mild disease in children, the primary medical danger of rubella is the infection of pregnant women, which may cause congenital rubella syndrome in developing babies.