Meningitis is an inflammation of the meninges, the membranes that cover the brain and spinal cord. It is usually caused by bacteria or viruses, but it can also be caused by certain medications or illnesses.

Meningitis is an inflammation of the meninges, the membranes that cover the brain and spinal cord. It is usually caused by bacteria or viruses, but it can also be caused by certain medications or illnesses. Bacterial meningitis is rare, but is usually serious and can be life-threatening if it's not treated right away. Viral meningitis (also called aseptic meningitis) is relatively common and far less serious. It often remains undiagnosed because its symptoms can be similar to those of the common flu.

Kids of any age can get meningitis, but because it can be easily spread between people living in close quarters, teens, college students, and boarding-school students are at higher risk for infection.

If dealt with promptly, meningitis can be treated successfully. So it's important to get routine vaccinations, know the signs of meningitis, and if you suspect that your child has the illness, seek medical care right away.

Causes of Meningitis

Many of the bacteria and viruses that cause meningitis are fairly common and are typically associated with other routine illnesses. Bacteria and viruses that infect the skin, urinary system, gastrointestinal or respiratory tract can spread by the bloodstream to the meninges through cerebrospinal fluid, the fluid that circulates in and around the spinal cord.

In some cases of bacterial meningitis, the bacteria spread to the meninges from a severe head trauma or a severe local infection, such as a serious ear infection (otitis media) or nasal sinus infection (sinusitis).

Many different types of bacteria can cause bacterial meningitis. In newborns, the most common causes are Group B streptococcus, Escherichia coli, and Listeria monocytogenes. In older kids, Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) and Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcus) are more often the causes.

Another bacteria, Haemophilus influenza type b (Hib), can also cause the illness but because of widespread childhood immunization, these cases are now rarer.

Similarly, many different viruses can lead to viral meningitis, including enteroviruses (such as coxsackievirus, poliovirus, and hepatitis A) and the herpesvirus.

Symptoms of Meningitis

The symptoms of meningitis vary and depend both on the age of the child and on the cause of the infection. Because the flu-like symptoms can be similar in both types of meningitis, particularly in the early stages, and bacterial meningitis can be very serious, it's important to quickly diagnose an infection.

The first symptoms of bacterial or viral meningitis can come on quickly or surface several days after a child has had a cold and runny nose, diarrhea and vomiting, or other signs of an infection. Common symptoms include:

- fever

- lethargy (decreased consciousness)

- irritability

- headache

- photophobia (eye sensitivity to light)

- stiff neck

- skin rashes

- seizures

Infants with meningitis may not have those symptoms, and might simply be extremely irritable, lethargic, or have a fever. They may be difficult to comfort, even when they are picked up and rocked.

Other symptoms of meningitis in infants can include:

- jaundice (a yellowish tint to the skin)

- stiffness of the body and neck (neck rigidity)

- fever or lower-than-normal temperature

- poor feeding

- a weak suck

- a high-pitched cry

- bulging fontanelles (the soft spot at the top/front of the baby's skull)

Viral meningitis tends to cause flu-like symptoms, such as fever and runny nose, and may be so mild that the illness goes undiagnosed. Most cases of viral meningitis resolve completely within 7 to 10 days, without any complications or need for treatment.

Treatment

Because bacterial meningitis can be so serious, if you suspect that your child has any form of meningitis, it's important to see the doctor right away.

If the doctor suspects meningitis, he or she will order laboratory tests to help make the diagnosis. The tests will likely include a lumbar puncture (spinal tap) to collect a sample of spinal fluid. This test will show any signs of inflammation, and whether a virus or bacteria is causing the infection.

A child who has viral meningitis may be hospitalized, although some kids are allowed to recover at home if they are not too ill. Treatment, including rest, fluids, and over-the-counter pain medication, is given to relieve symptoms.

If bacterial meningitis is diagnosed — or even suspected — doctors will start intravenous (IV) antibiotics as soon as possible. Fluids may be given to replace those lost to fever, sweating, vomiting, and poor appetite, and corticosteroids may help reduce inflammation of the meninges, depending on the cause of the disease.

Complications of bacterial meningitis can require additional treatment. For example, anticonvulsants might be given for seizures. If a child develops shock or low blood pressure, additional IV fluids and certain medications may be given to increase blood pressure. Some kids may need supplemental oxygen or mechanical ventilation if they have difficulty breathing.

Some patients who have had meningitis may require longer follow-up. One of the most common problems resulting from bacterial meningitis is impaired hearing, and kids who've had bacterial meningitis should have a hearing test following their recovery.

The complications of bacterial meningitis can be severe and include neurological problems such as hearing loss, visual impairment, seizures, and learning disabilities. The heart, kidneys, and adrenal glands also may be affected. Although some kids develop long-lasting neurological problems, most who receive prompt diagnosis and treatment recover fully.

How Does Meningitis Spread?

Most cases of meningitis — both viral and bacterial — result from infections that are contagious, spread via tiny drops of fluid from the throat and nose of someone who is infected. The drops may become airborne when the person coughs, laughs, talks, or sneezes. They then can infect others when people breathe them in or touch the drops and then touch their own noses or mouths.

Sharing food, drinking glasses, eating utensils, tissues, or towels all can transmit infection as well. Some infectious organisms can spread through a person's stool, and someone who comes in contact with the stool — such as a child in day care — may contract the infection.

The infections most often spread between people who are in close contact, such as those who live together or people who are exposed by kissing or sharing eating utensils. Casual contact at school or work with someone who has one of these infections usually will not transmit the infectious agent.

Prevention

Routine immunization can go a long way toward preventing meningitis. The vaccines against Hib, measles, mumps, polio, meningococcus, and pneumococcus can protect against meningitis caused by these microorganisms. Some high-risk children also should be immunized against certain other types of pneumococcus.

Doctors now recommend that kids who are 11 years old get vaccinated for meningococcal disease, a serious bacterial infection that can lead to meningitis. The vaccine is called quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine, or MCV4. Children who have not had the vaccine and are over 11 years old should also be immunized, particularly if they're going to college, boarding school, camp, or other settings where they are going to be living in close quarters with others. This vaccine may also be recommended for people who are traveling to countries where meningitis is more common.

Many of the bacteria and viruses that are responsible for meningitis are fairly common. Good hygiene is an important way to prevent any infection. Encourage kids to wash their hands thoroughly and often, particularly before eating and after using the bathroom. Avoiding close contact with someone who is obviously ill and not sharing food, drinks, or eating utensils can help halt the spread of germs as well.

In certain cases, doctors may decide to give antibiotics to anyone who has been in close contact with the person who is ill to help prevent additional cases of illness.

When to Call the Doctor

Seek medical attention immediately if you suspect your child has meningitis or if your child exhibits symptoms such as vomiting, headache, lethargy or confusion, neck stiffness, rash, and fever. Infants who have fever, irritability, poor feeding, and lethargy should also be assessed by a doctor right away.

If your child has had contact with someone who has meningitis (for example, in a child-care center or a college dorm), call your doctor to ask whether preventive medication is recommended.

Measles, also called rubeola, is a highly contagious respiratory infection that's caused by a virus. It causes a total-body skin rash and flu-like symptoms, including a fever, cough, and runny nose. Though rare in the United States, 20 million cases occur worldwide every year.

Measles, also called rubeola, is a highly contagious respiratory infection that's caused by a virus. It causes a total-body skin rash and flu-like symptoms, including a fever, cough, and runny nose. Though rare in the United States, 20 million cases occur worldwide every year.  Mad cow disease has been in the headlines in recent years. While a serious illness, it primarily affects cattle and, possibly, other animals, like goats and sheep — the risk to human beings is extremely low.

Mad cow disease has been in the headlines in recent years. While a serious illness, it primarily affects cattle and, possibly, other animals, like goats and sheep — the risk to human beings is extremely low.  Listeria infections (known as listeriosis) are caused by the bacterium Listeria monocytogenes.

Listeria infections (known as listeriosis) are caused by the bacterium Listeria monocytogenes.  Caring for pets offers a tremendous learning experience for kids, teaching them responsibility, gentleness, and respect for nature and other living beings. Like adults, kids can benefit from the companionship, affection, and relationships they share with their pets.

Caring for pets offers a tremendous learning experience for kids, teaching them responsibility, gentleness, and respect for nature and other living beings. Like adults, kids can benefit from the companionship, affection, and relationships they share with their pets.  Infant botulism is an illness that can occur when an infant ingests bacteria that produce a toxin inside the body. The condition can be frightening because it can cause muscle weakness and breathing problems. But it is very rare: Fewer than 100 cases of infant botulism occur each year in the United States, and most babies who do get botulism recover fully.

Infant botulism is an illness that can occur when an infant ingests bacteria that produce a toxin inside the body. The condition can be frightening because it can cause muscle weakness and breathing problems. But it is very rare: Fewer than 100 cases of infant botulism occur each year in the United States, and most babies who do get botulism recover fully.  Impetigo, a contagious skin infection that usually produces blisters or sores on the face and hands, is one of the most common skin infections among kids.

Impetigo, a contagious skin infection that usually produces blisters or sores on the face and hands, is one of the most common skin infections among kids.  Impetigo may affect skin anywhere on the body but commonly occurs around the nose and mouth, hands, and forearms.

Impetigo may affect skin anywhere on the body but commonly occurs around the nose and mouth, hands, and forearms. The word hepatitis simply means an inflammation of the liver without pinpointing a specific cause. Someone with hepatitis may:

The word hepatitis simply means an inflammation of the liver without pinpointing a specific cause. Someone with hepatitis may:  Gonorrhea is a sexually transmitted disease (STD) caused by a bacterium called Neisseria gonorrhoeae. It can also be transmitted from pregnant mothers to their babies at birth.

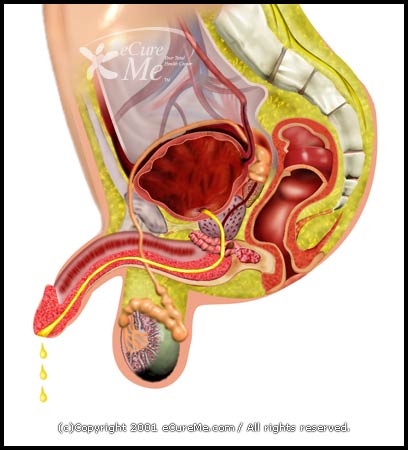

Gonorrhea is a sexually transmitted disease (STD) caused by a bacterium called Neisseria gonorrhoeae. It can also be transmitted from pregnant mothers to their babies at birth.  Encephalitis literally means an inflammation of the brain, but it usually refers to brain inflammation caused by a virus. It's a rare disease that occurs in approximately 0.5 per 100,000 individuals — most commonly in children, the elderly, and people with weakened immune systems (i.e., those with HIV/AIDS or cancer).

Encephalitis literally means an inflammation of the brain, but it usually refers to brain inflammation caused by a virus. It's a rare disease that occurs in approximately 0.5 per 100,000 individuals — most commonly in children, the elderly, and people with weakened immune systems (i.e., those with HIV/AIDS or cancer).