Roseola (also known as sixth disease, exanthem subitum, and roseola infantum) is a viral illness in young children, most commonly affecting those between the ages of 6 months and 2 years. It is typically marked by several days of high fever, followed by a distinctive rash just as the fever breaks.

Roseola (also known as sixth disease, exanthem subitum, and roseola infantum) is a viral illness in young children, most commonly affecting those between the ages of 6 months and 2 years. It is typically marked by several days of high fever, followed by a distinctive rash just as the fever breaks. Two common and closely related viruses can cause roseola: human herpesvirus (HHV) type 6 and possibly type 7. These two viruses belong to the same family as the better-known herpes simplex viruses (HSV), but HHV-6 and HHV-7 do not cause the cold sores and genital herpes infections that HSV can cause.

Signs and Symptoms

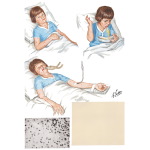

A child with roseola typically develops a mild upper respiratory illness, followed by a high fever (often over 103° Fahrenheit, or 39.5° Celsius) for up to a week. During this time, the child may appear fussy or irritable and may have a decreased appetite and swollen lymph nodes (glands) in the neck.

The high fever often ends abruptly, and at about the same time a pinkish-red flat or raised rash appears on the child's trunk and spreads over the body. The rash's spots blanch (turn white) when you touch them, and individual spots may have a lighter "halo" around them. The rash usually spreads to the neck, face, arms, and legs.

The fast-rising fever that comes with roseola triggers febrile seizures (convulsions caused by high fevers) in about 10% to 15% of young children. Signs of a febrile seizure include:

- unconsciousness

- 2 to 3 minutes of jerking or twitching in the arms, legs, or face

- loss of control of the bladder or bowels

Contagiousness

Roseola is contagious and spreads through tiny drops of fluid from the nose and throat of infected people. These drops are expelled when the infected person talks, laughs, sneezes, or coughs. Then if other people breathe the drops in or touch them and then touch their own noses or mouths, they can become infected as well.

The viruses that cause roseola do not appear to be spread by kids while they are exhibiting symptoms of the illness. Instead, someone who has not yet developed symptoms often spreads the infection.

Prevention

There is no known way to prevent the spread of roseola. Because the infection usually affects young children but rarely adults, it is thought that a bout of roseola in childhood may provide some lasting immunity to the illness. Repeat cases of roseola may occur, but they are not common.

Duration

The fever of roseola lasts from 3 to 7 days, followed by a rash lasting from hours to a few days.

Professional Treatment

To make a diagnosis, your doctor first will take a history and do a thorough physical examination. A diagnosis of roseola is often uncertain until the fever drops and the rash appears, so the doctor may order tests to make sure that the fever is not caused by another type of infection.

The illness typically does not require professional treatment, and when it does, most treatment is aimed at reducing the high fever. Antibiotics cannot treat roseola because a virus, not a bacterium, causes it.

Home Treatment

Until the fever drops, you can help keep your child cool using a sponge or towel soaked in lukewarm water. Do not use ice, cold water, alcohol rubs, fans, or cold baths. Acetaminophen (such as Tylenol) or ibuprofen (such as Advil or Motrin) can help to reduce your child's fever. Avoid giving aspirin to a child who has a viral illness because the use of aspirin in such cases has been associated with the development of Reye syndrome, which can lead to liver failure and death.

To prevent dehydration from the fever, encourage your child to drink clear fluids such as water with ice chips, children's electrolyte solutions, flat sodas like ginger ale or lemon-lime (stir room-temperature soda until the fizz disappears), or clear broth. If you are still breastfeeding, breast milk can help prevent dehydration as well.

When to Call the Doctor

Call the doctor if your child is lethargic or not drinking or if you cannot keep the fever down. If your child has a seizure, seek emergency care immediately.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is a bacterial infection that's transmitted to people by tick bites. It occurs most often in the spring and summer, during months when ticks are active — between April and early September.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is a bacterial infection that's transmitted to people by tick bites. It occurs most often in the spring and summer, during months when ticks are active — between April and early September.  Reye syndrome, an extremely rare but serious illness that can affect the brain and liver, occurs most commonly in kids recovering from a viral infection.

Reye syndrome, an extremely rare but serious illness that can affect the brain and liver, occurs most commonly in kids recovering from a viral infection.