Things That Can Go Wrong With the Immune System

Disorders of the immune system can be broken down into four main categories:

- immunodeficiency disorders (primary or acquired)

- autoimmune disorders (in which the body's own immune system attacks its own tissue as foreign matter)

- allergic disorders (in which the immune system overreacts in response to an antigen)

- cancers of the immune system

Immunodeficiency Disorders

Immunodeficiencies occur when a part of the immune system is not present or is not working properly. Sometimes a person is born with an immunodeficiency — these are called primary immunodeficiencies. (Although primary immunodeficiencies are conditions that a person is born with, symptoms of the disorder sometimes may not show up until later in life.) Immunodeficiencies can also be acquired through infection or produced by drugs. These are sometimes called secondary immunodeficiencies.

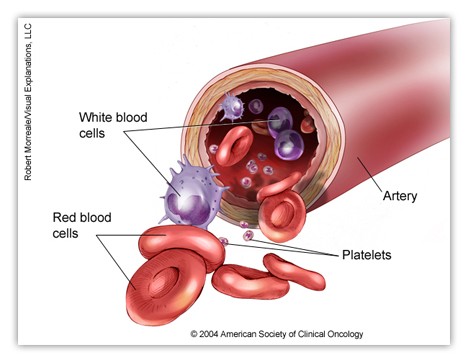

Immunodeficiencies can affect B lymphocytes, T lymphocytes, or phagocytes. Some examples of primary immunodeficiencies that can affect kids and teens are:

- IgA deficiency is the most common immunodeficiency disorder. IgA is an immunoglobulin that is found primarily in the saliva and other body fluids that help guard the entrances to the body. IgA deficiency is a disorder in which the body doesn't produce enough of the antibody IgA. People with IgA deficiency tend to have allergies or get more colds and other respiratory infections, but the condition is usually not severe.

- Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) is also known as the "bubble boy disease" after a Texas boy with SCID who lived in a germ-free plastic bubble. SCID is a serious immune system disorder that occurs because of a lack of both B and T lymphocytes, which makes it almost impossible to fight infections.

- DiGeorge syndrome (thymic dysplasia), a birth defect in which children are born without a thymus gland, is an example of a primary T-lymphocyte disease. The thymus gland is where T lymphocytes normally mature.

- Chediak-Higashi syndrome and chronic granulomatous disease both involve the inability of the neutrophils to function normally as phagocytes.

Acquired immunodeficiencies usually develop after a person has a disease, although they can also be the result of malnutrition, burns, or other medical problems. Certain medicines also can cause problems with the functioning of the immune system. Secondary immunodeficiencies include:

- HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) infection/AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) is a disease that slowly and steadily destroys the immune system. It is caused by HIV, a virus which wipes out certain types of lymphocytes called T-helper cells. Without T-helper cells, the immune system is unable to defend the body against normally harmless organisms, which can cause life-threatening infections in people who have AIDS. Newborns can get HIV infection from their mothers while in the uterus, during the birth process, or during breastfeeding. People can get HIV infection by having unprotected sexual intercourse with an infected person or from sharing contaminated needles for drugs, steroids, or tattoos.

- Immunodeficiencies caused by medications. Some medicines suppress the immune system. One of the drawbacks of chemotherapy treatment for cancer, for example, is that it not only attacks cancer cells, but other fast-growing, healthy cells, including those found in the bone marrow and other parts of the immune system. In addition, people with autoimmune disorders or who have had organ transplants may need to take immunosuppressant medications. These medicines can also reduce the immune system's ability to fight infections and can cause secondary immunodeficiency.

Autoimmune Disorders

In autoimmune disorders, the immune system mistakenly attacks the body's healthy organs and tissues as though they were foreign invaders. Autoimmune diseases include:

- Lupus is a chronic disease marked by muscle and joint pain and inflammation. The abnormal immune response may also involve attacks on the kidneys and other organs.

- Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis is a disease in which the body's immune system acts as though certain body parts such as the joints of the knee, hand, and foot are foreign tissue and attacks them.

- Scleroderma is a chronic autoimmune disease that can lead to inflammation and damage of the skin, joints, and internal organs.

- Ankylosing spondylitis is a disease that involves inflammation of the spine and joints, causing stiffness and pain.

- Juvenile dermatomyositis is a disorder marked by inflammation and damage of the skin and muscles.

Allergic Disorders

Allergic disorders occur when the immune system overreacts to exposure to antigens in the environment. The substances that provoke such attacks are called allergens. The immune response can cause symptoms such as swelling, watery eyes, and sneezing, and even a life-threatening reaction called anaphylaxis. Taking medications called antihistamines can relieve most symptoms. Allergic disorders include:

- Asthma, a respiratory disorder that can cause breathing problems, frequently involves an allergic response by the lungs. If the lungs are oversensitive to certain allergens (like pollen, molds, animal dander, or dust mites), it can trigger breathing tubes in the lungs to become narrowed, leading to reduced airflow and making it hard for a person to breathe.

- Eczema is an itchy rash also known as atopic dermatitis. Although atopic dermatitis is not necessarily caused by an allergic reaction, it more often occurs in kids and teens who have allergies, hay fever, or asthma or who have a family history of these conditions.

- Allergies of several types can occur in kids and teens. Environmental allergies (to dust mites, for example), seasonal allergies (such as hay fever), drug allergies (reactions to specific medications or drugs), food allergies (such as to nuts), and allergies to toxins (bee stings, for example) are the common conditions people usually refer to as allergies.

Cancers of the Immune System

Cancer occurs when cells grow out of control. This can also happen with the cells of the immune system. Lymphoma involves the lymphoid tissues and is one of the more common childhood cancers. Leukemia, which involves abnormal overgrowth of leukocytes, is the most common childhood cancer. With current medications most cases of both types of cancer in kids and teens are curable.

Although immune system disorders usually can't be prevented, you can help your child's immune system stay stronger and fight illnesses by staying informed about your child's condition and working closely with your doctor.

All living things reproduce. Reproduction — the process by which organisms make more organisms like themselves — is one of the things that sets living things apart from nonliving things. But even though the reproductive system is essential to keeping a species alive, unlike other body systems it's not essential to keeping an individual alive.

All living things reproduce. Reproduction — the process by which organisms make more organisms like themselves — is one of the things that sets living things apart from nonliving things. But even though the reproductive system is essential to keeping a species alive, unlike other body systems it's not essential to keeping an individual alive.