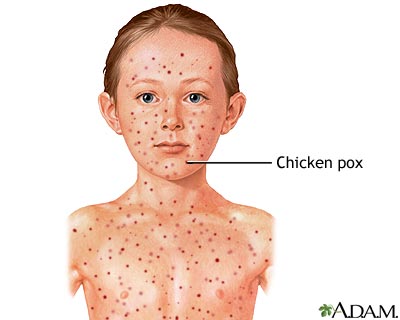

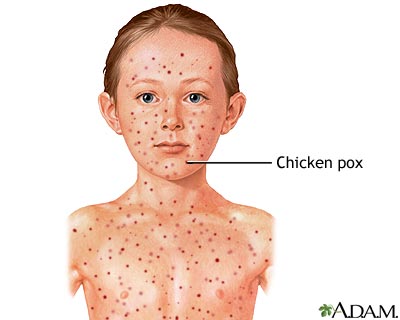

Chickenpox is a common illness among kids, particularly those under age 12. An itchy rash of spots that look like blisters can appear all over the body and may be accompanied by flu-like symptoms. Symptoms usually go away without treatment, but because the infection is very contagious, an infected child should stay home and rest until the symptoms are gone.

Chickenpox is caused by the varicella-zoster virus (VZV). Kids can be protected from VZV by getting the chickenpox (varicella) vaccine, usually between the ages of 12 to 15 months. In 2006, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended a booster shot at 4 to 6 years old for further protection. The CDC also recommends that people 13 years of age and older who have never had chickenpox or received chickenpox vaccine get two doses of the vaccine at least 28 days apart.

A person usually has only one episode of chickenpox, but VZV can lie dormant within the body and cause a different type of skin eruption later in life called shingles (or herpes zoster). Getting the chickenpox vaccine significantly lowers your child's chances of getting chickenpox, but he or she may still develop shingles later.

Symptoms of Chickenpox

Chickenpox causes a red, itchy rash on the skin that usually appears first on the abdomen or back and face, and then spreads to almost everywhere else on the body, including the scalp, mouth, nose, ears, and genitals.

The rash begins as multiple small, red bumps that look like pimples or insect bites. They develop into thin-walled blisters filled with clear fluid, which becomes cloudy. The blister wall breaks, leaving open sores, which finally crust over to become dry, brown scabs.

Chickenpox blisters are usually less than a quarter of an inch wide, have a reddish base, and appear in bouts over 2 to 4 days. The rash may be more extensive or severe in kids who have skin disorders such as eczema.

Some kids have a fever, abdominal pain, sore throat, headache, or a vague sick feeling a day or 2 before the rash appears. These symptoms may last for a few days, and fever stays in the range of 100°–102° Fahrenheit (37.7°–38.8° Celsius), though in rare cases may be higher. Younger kids often have milder symptoms and fewer blisters than older children or adults.

Typically, chickenpox is a mild illness, but can affect some infants, teens, adults, and people with weak immune systems more severely. Some people can develop serious bacterial infections involving the skin, lungs, bones, joints, and the brain (encephalitis). Even kids with normal immune systems can occasionally develop complications, most commonly a skin infection near the blisters.

Anyone who has had chickenpox (or the chickenpox vaccine) as a child is at risk for developing shingles later in life, and up to 20% do. After an infection, VZV can remain inactive in nerve cells near the spinal cord and reactivate later as shingles, which can cause tingling, itching, or pain followed by a rash with red bumps and blisters. Shingles is sometimes treated with antiviral drugs, steroids, and pain medications, and in May 2006 the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a vaccine to prevent shingles in people 60 and older.

Contagiousness

Chickenpox is contagious from about 2 days before the rash appears and lasts until all the blisters are crusted over. A child with chickenpox should be kept out of school until all blisters have dried, usually about 1 week. If you're unsure about whether your child is ready to return to school, ask your doctor.

Chickenpox is very contagious — most kids with a sibling who's been infected will get it as well, showing symptoms about 2 weeks after the first child does. To help keep the virus from spreading, make sure your kids wash their hands frequently, particularly before eating and after using the bathroom. And keep a child with chickenpox away from unvaccinated siblings as much as possible.

People who haven't had chickenpox also can catch it from someone with shingles, but they cannot catch shingles itself. That's because shingles can only develop from a reactivation of VZV in someone who has previously had chickenpox.

Chickenpox and Pregnancy

Pregnant women and anyone with immune system problems should not be near a person with chickenpox. If a pregnant woman who hasn't had chickenpox in the past contracts it (especially in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy), the fetus is at risk for birth defects and she is at risk for more health complications than if she'd been infected when she wasn't pregnant. If she develops chickenpox just before or after the child is born, the newborn is at risk for serious health complications. There is no risk to the developing baby if the woman develops shingles during the pregnancy.

If a pregnant woman has had chickenpox before the pregnancy, the baby will be protected from infection for the first few months of life, since the mother's immunity gets passed on to the baby through the placenta and breast milk.

Those at risk for severe disease or serious complications — such as newborns whose mothers had chickenpox at the time of delivery, patients with leukemia or immune deficiencies, and kids receiving drugs that suppress the immune system — may be given varicella zoster immune globulin after exposure to chickenpox to reduce its severity.

Preventing Chickenpox

Doctors recommend that kids receive the chickenpox vaccine when they are 12 to 15 months old and a booster shot at 4 to 6 years old. The vaccine is about 70% to 85% effective at preventing mild infection, and more than 95% effective in preventing moderate to severe forms of the infection. Although the vaccine works pretty well, some kids who are immunized still will get chickenpox. Those who do, though, will have much milder symptoms than those who haven't had the vaccine and become infected.

Healthy children who have had chickenpox do not need the vaccine — they usually have lifelong protection against the illness.

Treating Chickenpox

A virus causes chickenpox, so the doctor won't prescribe antibiotics. However, antibiotics may be required if the sores become infected by bacteria. This is pretty common among kids because they often scratch and pick at the blisters.

The antiviral medicine acyclovir may be prescribed for people with chickenpox who are at risk for complications. The drug, which can make the infection less severe, must be given within the first 24 hours after the rash appears. Acyclovir can have significant side effects, so it is only given when necessary. Your doctor can tell you if the medication is right for your child.

Dealing With the Discomfort of Chickenpox

You can help relieve the itchiness, fever, and discomfort of chickenpox by:

- Using cool wet compresses or giving baths in cool or lukewarm water every 3 to 4 hours for the first few days. Oatmeal baths, available at the supermarket or pharmacy, can help to relieve itching. (Baths do not spread chickenpox.)

- Patting (not rubbing) the body dry.

- Putting calamine lotion on itchy areas (but don't use it on the face, especially near the eyes).

- Giving your child foods that are cold, soft, and bland because chickenpox in the mouth may make drinking or eating difficult. Avoid feeding your child anything highly acidic or especially salty, like orange juice or pretzels.

- Asking your doctor or pharmacist about pain-relieving creams to apply to sores in the genital area.

- Giving your child acetaminophen regularly to help relieve pain if your child has mouth blisters.

- Asking the doctor about using over-the-counter medication for itching.

Never use aspirin to reduce pain or fever in children with chickenpox because aspirin has been associated with the serious disease Reye syndrome, which can lead to liver failure and even death.

As much as possible, discourage kids from scratching. This can be difficult for them, so consider putting mittens or socks on your child's hands to prevent scratching during sleep. In addition, trim fingernails and keep them clean to help lessen the effects of scratching, including broken blisters and infection.

Most chickenpox infections require no special medical treatment. But sometimes, there are problems. Call the doctor if your child:

- has fever that lasts for more than 4 days or rises above 102° Fahrenheit (38.8° Celsius)

- has a severe cough or trouble breathing

- has an area of rash that leaks pus (thick, discolored fluid) or becomes red, warm, swollen, or sore

- has a severe headache

- is unusually drowsy or has trouble waking up

- has trouble looking at bright lights

- has difficulty walking

- seems confused

- seems very ill or is vomiting

- has a stiff neck

Call your doctor if you think your child has chickenpox, if you have a question, or if you're concerned about a possible complication. The doctor can guide you in watching for complications and in choosing medication to relieve itching. When taking your child to the doctor, let the office know in advance that your child might have chickenpox. It's important to ensure that other kids in the office are not exposed — for some of them, a chickenpox infection could cause severe complications.

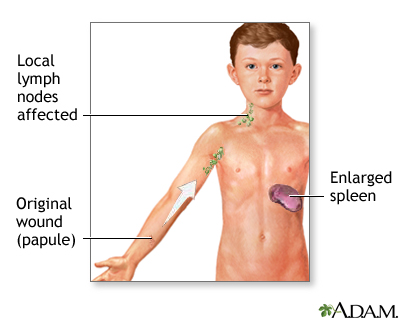

Lyme disease is an infection caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi. This bacterium is usually found in animals such as mice and deer. Ixodes ticks can pick up the bacteria when they bite an infected animal, then transmit it to a person, which can lead to Lyme disease.

Lyme disease is an infection caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi. This bacterium is usually found in animals such as mice and deer. Ixodes ticks can pick up the bacteria when they bite an infected animal, then transmit it to a person, which can lead to Lyme disease.